Some of the following is true.

It was late January. Overcast and lightly snowing. No hint of wind. Temperatures in the low twenties and dropping in the late afternoon. Silent, but not serene.

I sat half-buried in the avalanche debris with two broken legs. Blood had already filled my ski boots. My ski partner gave me some extra clothing for warmth and skied the ten miles out to the trailhead. There was no cell coverage, no nothing.

I thought of my son at the school playground wondering why I wasn’t there to pick him up. I thought of my ex-wife, angry, imagining that our son had been left, forgotten, just like those other times. I thought of my memorial and how an old climbing friend in the Tetons had said years ago that if I were taken early, there wouldn’t be a dry eye in the place. Others would say I died doing what I loved to do. I raged at this last thought and then it washed over me like a wave.

I thought of that time I was on a rescue near the summit of the Grand Teton withstanding yet another onslaught of sparks and lightning on the highest lightning rod in the range.

I thought of the time I swam across the Green River in Desolation Canyon without a life jacket. Just to see if I could. I remember getting just past half-way, realizing I had way underestimated the swiftness of the current and way overestimated by swimming ability. And then starting to take in water.

How many times had I made a deal with the devil? How many more had I made a deal with the devil and not even known I was so close? I thought of the young aviator St. Exupéry hearing from friend and mentor Mermoz, When that final smashup comes…it’s worth it.

I shuddered with both the cold and the grief and blacked out. There was no door and there was no light.

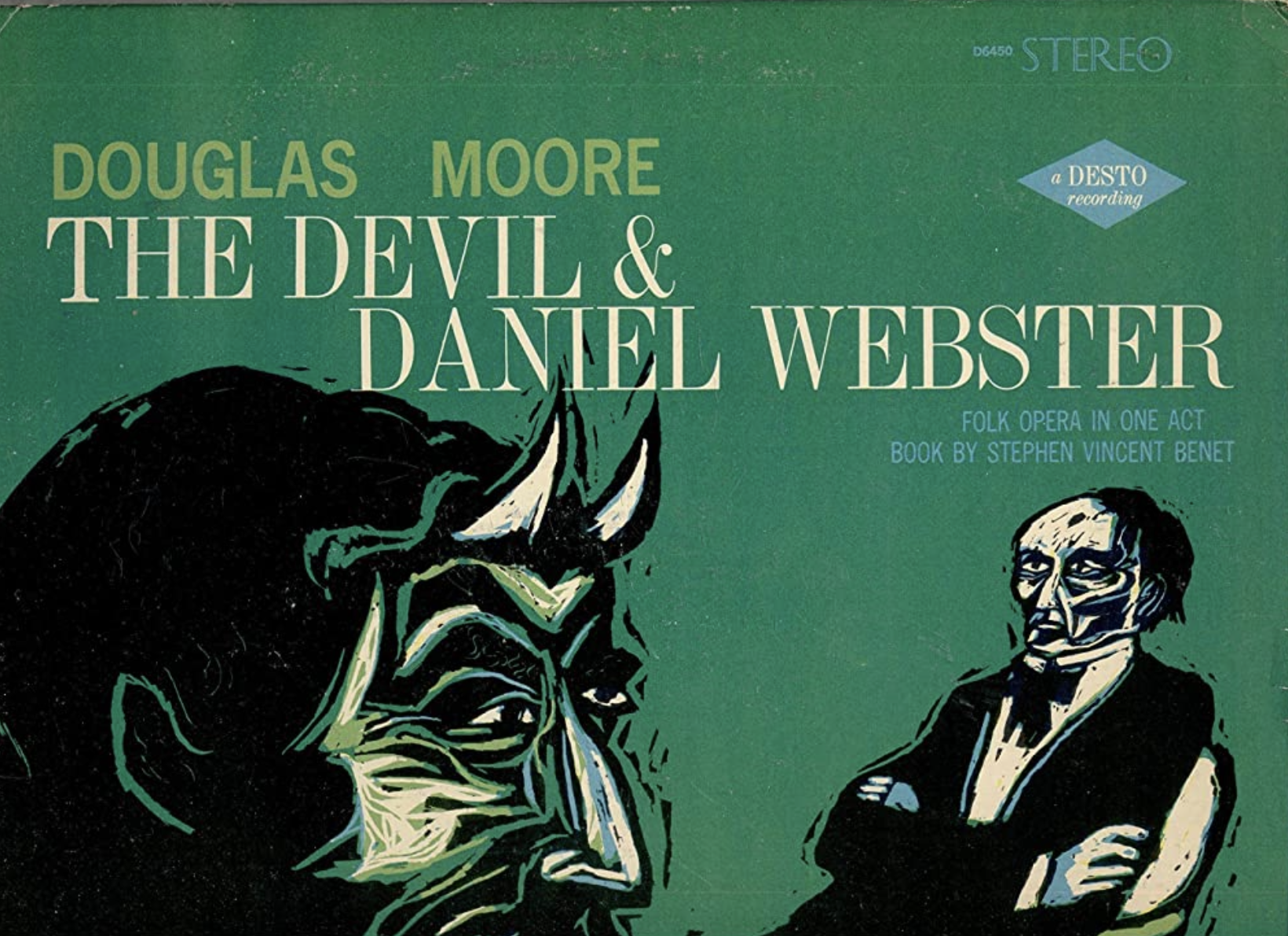

In Stephen Vincent Benét’s 1936 novella, The Devil and Daniel Webster, a poor farmer Jabez Stone looks over his barren fields and makes the deal. The devil – Scratch– promises to be back in six years. They shake hands and Stone feels a handshake as cold as ice.

Stone’s fields turn to gold nearly overnight. The cows got fat, and his horses sleek; he was soon one of the most prosperous people in the county. Six years go by and one dark summer night he hears a knock at the door. The door slowly opens and a dark figure stands at the doorway, lightning flashing in the dry summer heat. Behind him stand the damned with the fires of hell still upon them and if Jabez Stone had been sick with terror before, he was blind with terror now.

It’s beside the point that improbably, the most famous lawyer of the day, Dan’l Webster, eventually and successfully defends Jabez Stone in a courtroom when the jury is not one of Stone’s peers but the demons of Hell. We should all be so lucky.

What I want to know is this:

Do we make a deal with Death when we play games with risk?

There have many times when He has come to the door, heat lightning flashing in the distance. We talk, we bargain some more. For many of us, it was easy to shake hands those years back: Death being an abstraction, the subconscious mind unaware. These experiences, these thrills, they all meant so much and enriched our lives. We understood them. We didn’t understand Death and so it was easy to make the deal. Give me this life and you may come when you please, we said. But not for six years or more. The greatest two risks in life are risking too much and risking too little.

But know that at some point the Devil may get his due. Not always. But if He does, will it be worth the smashup in the end? It might very well be.

Previously published in Ascent Backcountry Journal

(Ed.note- I dare you to count the number of words in the main body of this piece…)