Roping the Wind (Slab)

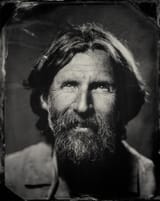

Years ago, I worked for a rancher in northeast Utah named James Gunn. Wranglers, boots, cowboy hat, the full deal. Hard saying if he was a philosopher on horseback or a cowboy who just contemplated life as is. One thing's for sure. James never missed an opportunity to tell a story or chew on some idea. After I left the ranch, he soon began to take clients, or "dudes" up on horseback into the Blue Mountains on the eastern slope of the Uintas. One day a client, after a particularly windy day, asked James why he never wore a stampede string to help keep his hat on. "A man's hat defines him," he said, "When his hat comes off, it's a sign. Time to take stock."

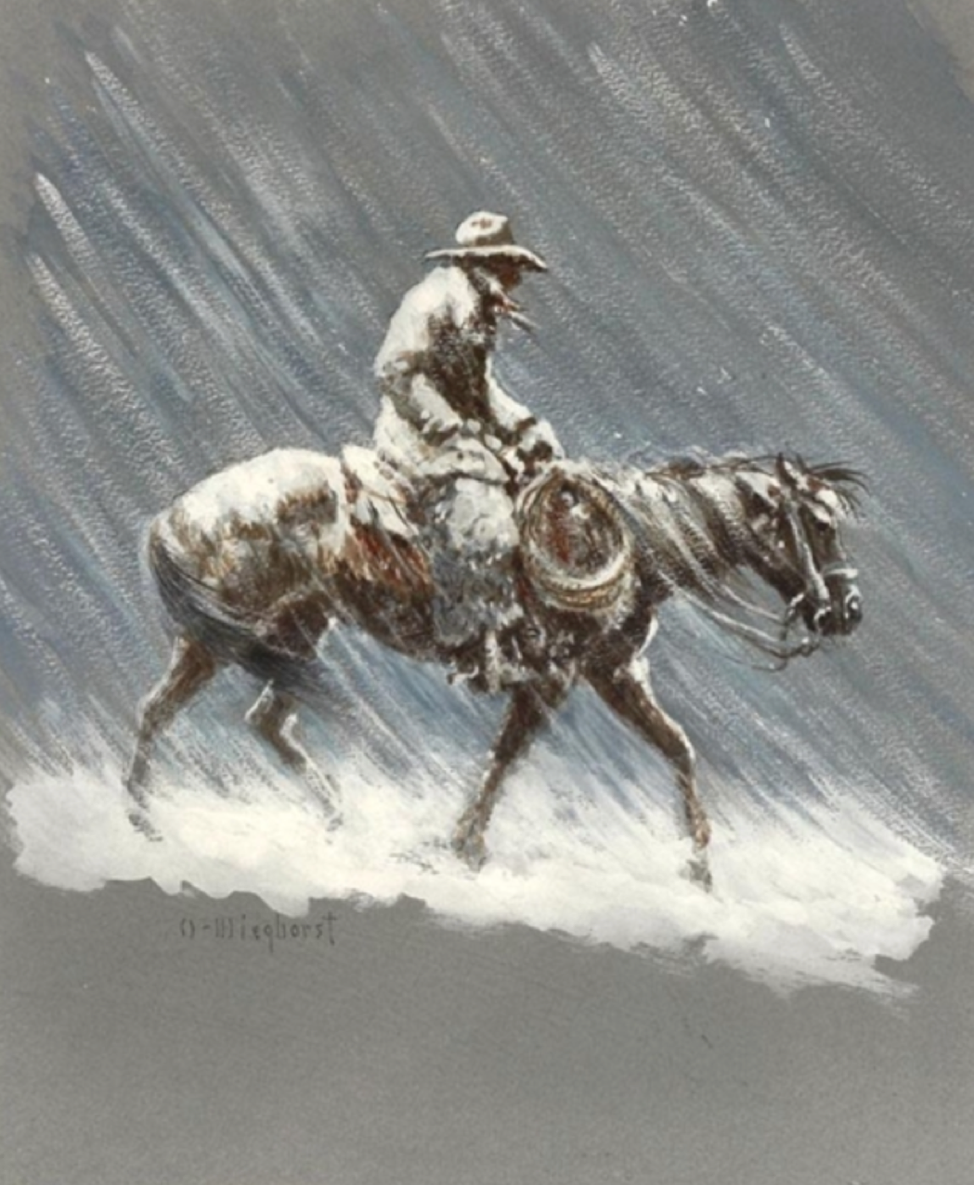

This morning I spoke with one of the two skiers involved in the Hogum Fork avalanche from Tuesday. Each are long time professional avalanche mitigators (that is, they get paid to trigger avalanches at one of the ski resorts) and most certainly know their way around avalanches in general and wind slabs in particular. Wind slabs are something that we can develop an expertise for with enough experience because much of the time, they offer direct and immediate feedback (unlike their persistent or deep slab cousins).

As the event played out, it was not the first but the second skier down the Hogum 200 that triggered the wind slab that carried him (and dusted the tails of his partner's skis) over 700' down the fall line, He lost some gear but otherwise ended up on top of the debris with only some bumps and bruises. "We had our eyes on the Sliver on the Thunder Ridge headwall and overlooked the "200" in order to get to the prize." Legend has it that a notorious long time Wasatch backcountry skier skiied the Hogum 200 with a cigarette in his mouth and so perhaps it would be easy terrain to overlook. The Sliver, on the other hand, as described in Andrew McLean's The Chuting Gallery is "an incredibly beautiful plumb line with a steep upper section, a gorgeous mid section and an excellent finishing apron." It's a steep 45° for much of its 1700' vertical drop.

It brought to mind scrambling terrain in the Tetons or other ranges around the West. Recently, after watching the Alex Honnold film Free Solo, the retired climbing ranger and forecaster Tom Kimbrough pointed out that most often, solo climbers slipped and fell in easy terrain well before, or just after, the crux section. At least the ones he knows of, anyway, and this spanned a climbing career of over sixty years. And counting. It brings about these ideas of mindfulness, the present moment, and the task at hand.

Before we hung up, I asked the skier why he had submitted a report to us at the Utah Avalanche Center. "Well," he said without having to think much about it, "that's what you do."

The slid skier may have lost his cowboy hat, but not his character.

Thanks for that.