Meditations on Skiing the No-Fall Zone

Mike Hattrup skiing the Idaho Express, GFT.

photo: Doug Workman

Two winters ago, my partner and I headed toward the Pine Hollow area in upper American Fork Canyon to access the north side of Timpanogos. It may be one of my favorite places in the entire Wasatch Range. We got a late start and worked through the Timponeeke campground, west into the Corner Pocket and then followed an efficiently-set skin track up through one of the weaknesses to gain the Woolley Hole. To our surprise (we were headed toward the Pika Cirque), and then - I can't think of a better word - appreciation - the skinner continued up the east facing ski runs of the Woolley Hole and entered the dark recesses of the Grunge Couloir. Later, I spoke at length with two of the party about skin tracks, ski mountaineering, and life. Very thoughtful, all.

The Grunge is not found in the old Wasatch Tours books by Hanscom and Kelner but the two do mention the Forked Tongue and Cold Fusion couloirs on the western side of the great north face. Andrew McLean's The Chuting Gallery, not surprisingly, does include the Grunge and describes it as "serene and soothing as a Mud Honey concert in a hurricane." From the north summit (elevation 11,100'), the couloir is mostly north-northeast facing but the top portion catches some early sun on it's west entry. The skiing vertical is roughly 1200' (roughly one-fifth of the vertical of Slide Canyon's immense relief on the southern end of the Timpanogos massif). The slope steepness at the top has been measured at 62°, but I suspect this depends on the season's wind loading and cornice development over the winter.

What is it about couloir skiing, ski mountaineering, and skiing the No-Fall Zone? I've skied the Grand, the Skillet, the north face of Timp, and others, but these are quite pedestrian, shall we say, by today's standards. But still. The reasons, the draw, the allure are many - fulfillment, challenge, an interesting way to tie in many skills and experience the mountains in interesting ways. But what they all involve is a different way to consider Risk. It involves all of the thrill and fulfillment of backcountry skiing and alpine climbing, as well as all of the attendant subjective and objective hazards.

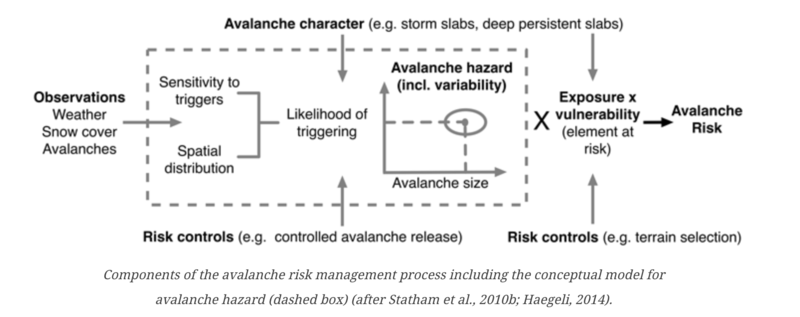

In 2010, the CMAH - the Conceptual Model of Avalanche Hazard - was established as a way to use standard risk metrics to determine avalanche hazard. Let's take a look at how it might apply to Ski Mountaineering in general - and Skiing the Grunge (and Forked Tongue) on Sunday.

Likelihood - this refers to how likely one might trigger an avalanche. It refers to not just sensitivity but spatial distribution (ie: isolated or widespread). In this case on Sunday the overall danger was rated as LOW. Cornices loomed over part of the couloir, yet temperatures were quite cold, the sun had yet to hit the cornices, and there was no additional snow or wind. These all played in favor of our protagonists. Similarly, snow conditions were "edge-able", allowing for good purchase on the way up and on the way down.

Consequence - this refers to size and in my own words, Manageability, of the avalanche. We rate avalanches on the Destructive scale on whether they are relatively harmless or whether they can take out an entire village. Manageability implies whether avalanches are generally predictable or not. Oversimplified, small to medium dry sluffs are manageable for experienced practitioners, hard slabs over surface hoar are not. In this case, the overall LOW takes this into account.

Exposure - this refers to your location in the terrain and directly impacts consequence. With general backcountry riding, it matters greatly if you are at the top of a fracturing slab avalanche or if it breaks 100' above you. Exposure obviously plays a huge role in ski mountaineering, where even a very small avalanche that knocks you off your feet can lead to disaster. Over cliffbands? Into a crevasse? Slide-for-life for thousands of feet? In this case, exposure plays the main card for the team in the Grunge for both the cornices above and the 1000' slide-for-life below. Here, fitness matters. The team was made up of thoroughbreds, able to minimize their overall exposure time in the couloir.

Vulnerability - this generally refers to how well we might be able to withstand the problems, per se. In the general avalanche world, having good partners and rescue gear and an avalanche airbag and/or avalung makes us less vulnerable to catastrophe. For the team, they had all the avalanche gear plus axes/whippets, crampons, and helmets that would help them climb but give them more secure footing if needed. Although, if you watched the film Free Solo, was Alex Honnold wearing a helmet? Of course not. It would be ridiculous to ridicule him for not wearing one.

McLean admits that the Grunge historically has been used as a spring mountaineering route for climbers with their ice axes and crampons. At that time of the year, one certainly must keep a keen eye out for rockfall, the steep runnel (as often found in steep spring couloirs) He goes on to say that "there are enough objective hazards to keep even the most attention deficit disordered grunge rocker's mind occupied." The sides are lined with towering, rotting rock walls that send down a constant barrage of buzzing missiles. Still, the "oh-dark-thirty" start stacked the odds in their favor to theoretically have these missiles still welded to the wall.

In the above, I use not just the term objective hazards, but subjective ones. Objective hazards include things like avalanches, rockfall, cornice fall, moats, thinly-covered water falls and creeks/fissures. These are generally known.

It's the subjective hazards which, to me, are fascinating and unique to each individual. Ian McCammon and others call then "personal disaster flags".

Where do we make our mistakes? Are there patterns to our mistakes?

And what about the proper mindset for the No-Fall Zone? There's a sweet spot that combines confidence and respect for the medium to ferry us to the other side. We also need to acknowledge that when we go into the mountains, we may never come back. This meditation on life and death and outcomes is critically important, but so is the timing of these meditations. These meditations should occur before and after the event but must be compartmentalized when in the medium.

I've talked more about compartmentalization as it applies to rescue and body recovery work in an interview HERE.

We are unaccustomed to being in the presence of death or nearness to the same and there are times when these very human thoughts and emotions must be tabled in order to get at the task at hand. Ever seen someone cognitively or even physically freeze when they look beyond the world into oblivion? What's challenging is that none of us have direct experience with our own mortality. It is an abstraction that we may never comprehend until it's too late. And maybe not then.

Lastly, we must leave the JUDGE behind. As I've written elsewhere, it's insulting at worst and a waste of time at best to look askance at others who are on either end of the pendulum. It's - how shall we say - inelegant to look upon some as suicidal and others as boring and unfulfilled. We cannot judge an event by outcomes alone, especially as our perception of the outcome and the final outcome may be different animals altogether. Ever thought that a book was over only to find that there were still four chapters left?

The two greatest risks are risking too much...and risking too little.

So - and thanks to the post on Instagram from last week - did they make the right call?

I think they did. But still - This isn't the most important question.