What is your Level of Acceptable Risk? How did you determine this? Some will center-punch Superior on a CONSIDERABLE danger while others feel happy going to Powder Park everyday. It’s insulting at worst and a waste of time at best to look askance at others who are on either end of the pendulum. It’s – how shall we say – inelegant to look upon some as suicidal and others as boring and unfulfilled. But –

The key points here are

- To be aware of your level of acceptable risk

- Understand factors that may influence your risk taking

- Find others who have a similar level of risk acceptance

Ok, now the math –

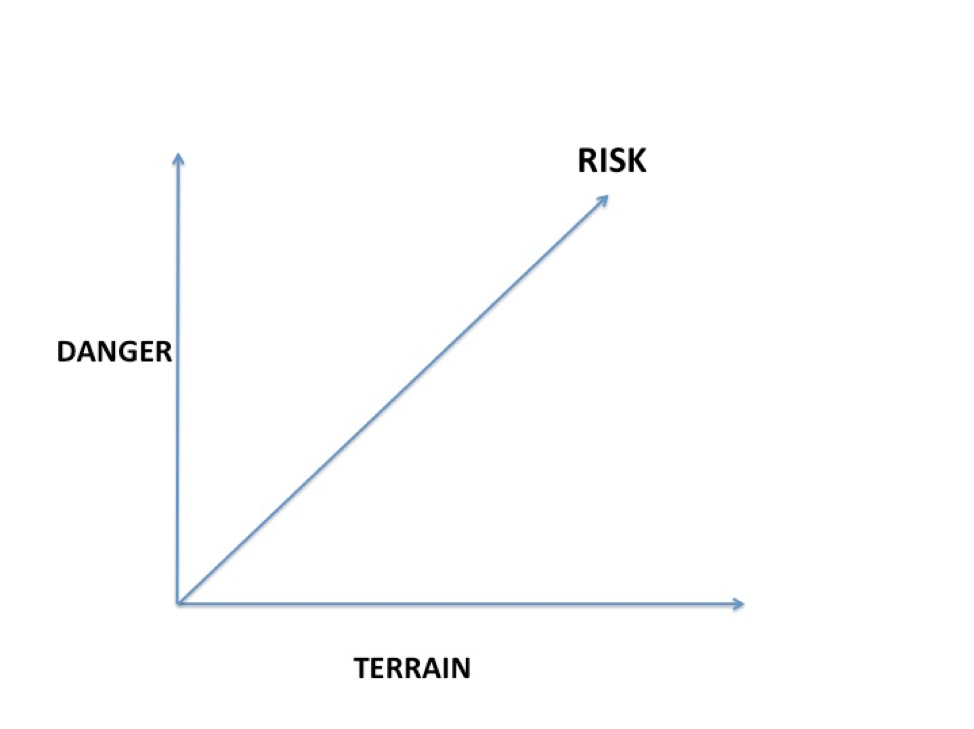

Essentially – RISK = Avalanche Danger times Mountain Terrain R=DxT

Here are the variables: D – Avalanche Danger/Danger Scale (Low, Moderate, Considerable, High, Extreme)

T – Mountain Terrain (Avalanche Terrain Exposure ie: Powder Park or Superior)

Here is the constant: R – RISK

KEY POINT: Now what this pre-supposes is that you want to keep your RISK at a constant level. If that’s the case, then D (Danger) and T (Mountain Terrain) must have an inverse relationship to one another. When the danger goes up, you scale down your terrain choices. When the danger goes down, perhaps you ‘up’ your terrain choices – otherwise, you’re taking less risk. And that’s ok too.

Easy, huh? Well, not so fast. It may be news to you that humans are complicated people.

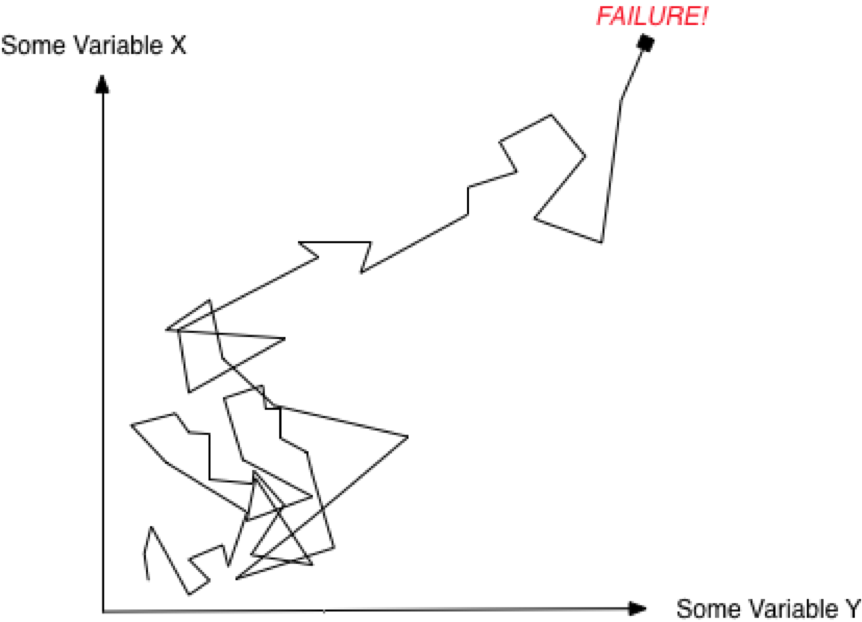

As it turns out, most of us feel like our decision-making looks like what you see on in the top figure.. What actually happens is in the bottom one.

The author Sidney Dekker, in his book Drift into Failure, posits that a “series of small relaxations on safety standards can lead to a catastrophic system failure. These systems drift and that from inside the system, such drift isn’t visible until the failure occurs.” Please read that sentence again – I had to.

So What? How does this apply to us in the avalanche world, particularly when it gets back to Math and especially when it applies to a Low Probability/High Consequence persistent slab problem? I’m glad you asked.

Here’s what happens –

- The danger is MODERATE OR CONSIDERABLE

- We choose appropriate terrain.

- We see no signs of avalanches.

- We see no shooting cracks. We hear or feel no collapsing or whumphing.

- Test results are inconclusive.

- Cornice drops and slope cuts provide no results.

- We see other tracks on the slope(s).

Now what?

- We “drift” into steeper terrain because we perceive the danger is lower than it actually is.

Result? You guessed it.

These are when conditions are the most tricky and dangerous. In reality, the danger remained the same, you’ve ‘upped’ your terrain choices…and therefore you’ve upped your RISK.

It’s common during persistent slab, deep slab, or hard wind slab conditions. It’s just part of the waiting game – and it takes discipline. These are times when we need to assume a “Ulysses contract” (common in medical and other situations). You’ll remember that Ulysses tied himself to the mast and had his men put wax in their ears to avoid the lure of the Sireens (as Delmar/Tim Blake Nelson called them in O Brother Where Art Thou). It worked for Ulysses, but it didn’t work for Delmar O’Donnell and Ulysses Everett McGill in O Brother,

Footage by Robert Crowe, circa early 1980s near Wolf Creek Pass in the south San Juans of Colorado. The 7th skier died in this avalanche, cause unknown. Buried weak layer was reported to be surface hoar.